Ŋaraka Ŋoyŋura – The Bones Beneath

31 Aug 2018

BUKU-LARRNGGAY MULKA CENTRE

SEARCY STREET GALLERY

9/41 Cavenagh Street Darwin

In a trendy gallery in Darwin in 2018 we sip chardonnay and chitter chat. It does not occur to us that we are connected to the deep ancient past when tsunamis rolled into Blue Mud Bay in the time before Pharaohs. But all around is the evidence of our connection. We are friends with the holders of the eyewitness accounts of this happening. It is real. Not to be dismissed as a ‘cultural’ thing or an ‘Aboriginal’ thing. Or even an ‘art’ thing.

But all around is the evidence of our connection. We are friends with the holders of the eyewitness accounts of this happening. It is real. Not to be dismissed as a ‘cultural’ thing or an ‘Aboriginal’ thing. Or even an ‘art’ thing.

There is no separate axis of time. The space/time continuum is not just a catchphrase from sci-fi sitcoms. That’s real too. The dimensions we live in are length, breadth, width and time. So time is a place. And all the times that have, or will exist, as places, are still in existence although the spotlight of our ‘now’ is not shining on them at the minute.

That waffly airy-fairy weird conjecture is not some distorted tribal nonsense. That’s Einstein. “The distinction between the past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.”

The deep meaning of the trite phrase Dreamtime which non-Indigenous Australians tout about probably escapes most users. It is a grammatic tense which does not exist in English but within which Yolŋu describe their cosmology. Possibly better translated as ‘everywhen’ — a contemporaneous past/present/future tense. This is the when of the occurrences described in these works.

If I said “Jesus was/is/will be crucified/being crucified/crucified” (which I can’t in any useful way say in English as this example proves neatly) it should impact you that, even as I speak, his lifeblood is eking out. I have your attention! We should do something about this RIGHT NOW!

The creation is not something that happened, and now we live in non-magical times, waiting for a later judgment. It has happened/ is happening/ will happen.

Whilst we are at it, in the mind-bending department, Yolŋu do not see water as a lifeless, homogenous, undifferentiated substance. Each body of water has a deeper identity. Each bay, each rivulet, each body of mist, each soak, swamp or spring appears in the songs and has a design. Each person emanates from and will return through these specific waters to a reservoir which nurtures their specific identity.

In the catalogue for the iconic ‘Saltwater; Yirrkala bark paintings of Sea Country’ exhibition which contributed to the achievement of Sea Rights, Barayuwa’s maternal uncle Dula Ŋurruwuthun (1936-2001) gave an extensive statement about the water depicted in these works.

“Sacred art that has been etched by the sea where the ocean named Wulamba roars.

The open sea Dhukthukpa (power name for this water body), ”Yidiŋimirri” (esoteric name of the resting place of the Shark), “Barrwalandji (the shelter of the Shark’s knowledge). The sound of the roaring waters, it is called Wulamba. The wide open sea has a huge tail of waves. Water that roars. This water exists in ‘ancestral times and the cycle continues. It is massive ancient endless infinity. We call this Gäpu-Dhä-yindi.”

What follows is a lengthy, esoteric exposition of the matrix of waters within which the estate depicted in these works, Yarrinya, sits. In the course of setting this out he says,

“And just over there is the open ocean Garrŋirr, Manbuyŋa (power names). There the water can strike you and shock you. And it is moving. Imitating the crocodile holding onto the water with arms outstretched. Over there at the tongue of the knife, Yikiŋuruya, Yikimula, Yarrwaŋa (power names for Yarrinya, Yirritja moiety, Munyuku clan body of water in Blue Mud Bay). A person preparing for conflict will dance imitating the turbulent sea at the bottom of the ocean. The white foam at the surface is the white clay of face paint.

Wurruymu (power name of stingray Ancestral being), Rrätj (power name of Yirritja saltwater area) commands action. Telling the child of that clan to be strong. The Djapu, our children, will do that. They will draw their strength and courage from that design. I am telling a true story. Not a lie.”

And here is Barayuwa Munuŋgurr, a Djapu clan man, the son of Dula’s sister drawing on that design of his mother clan, the Munyuku.

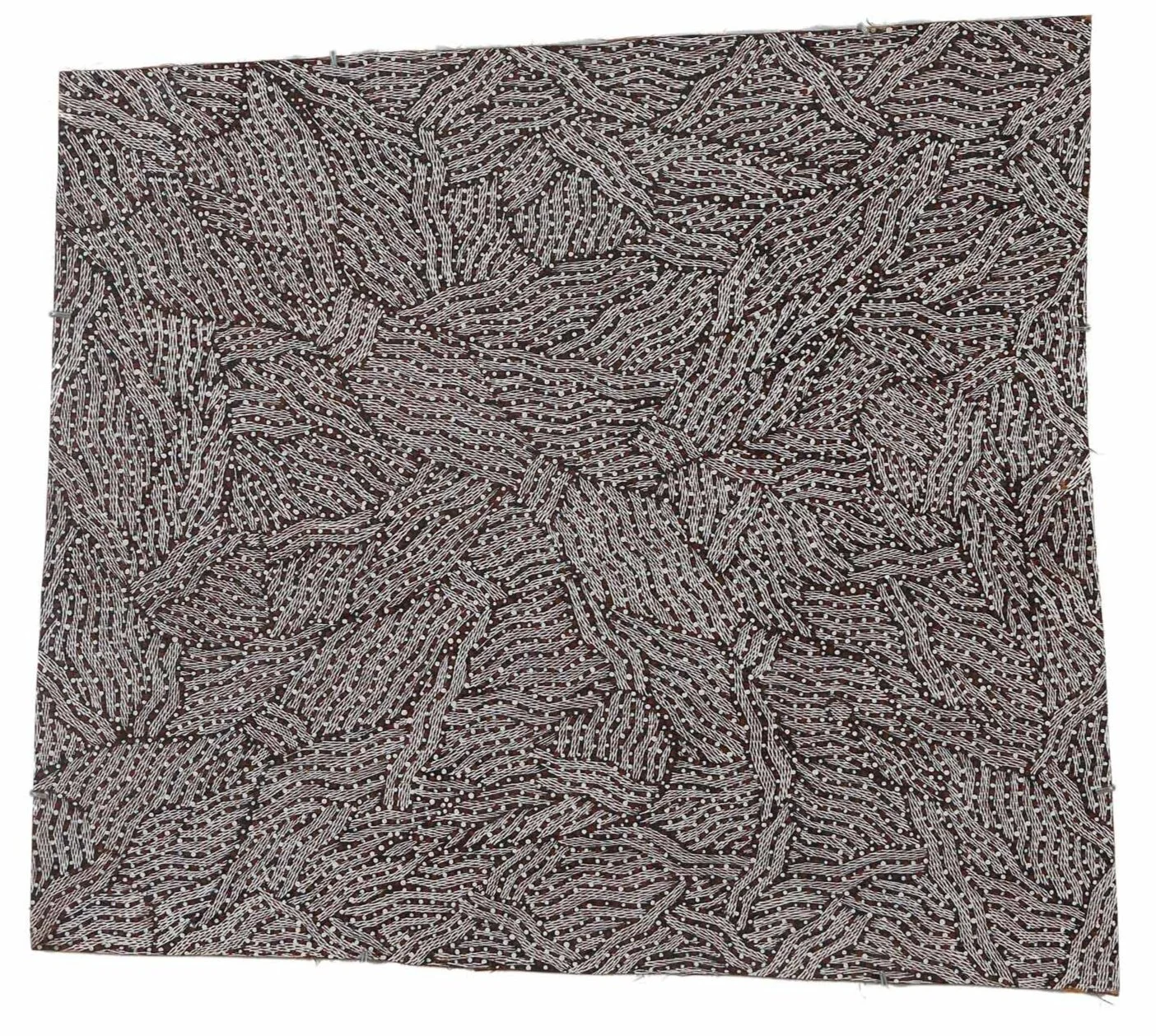

So what is in this design? What is etched into this place and into Barayuwa himself?

Yarrinya is known in English as Point Blane, although there are probably very few times that this name has ever been used except on maps.

A whale called Mirinyuŋu is/was/will be living in the ocean at Yarrinya. The whale, being Munyuku, was in its own country. Munyuku spirit men called Wurramala or Matjitji lived and hunted in this country. According to Yolŋu kinship classifications, the whale is the ‘brother’ of these men. They killed their brother Mirinyuŋu, who eventually washed up onto the beach, contaminating it with blood and fat turning putrid.

This is how the Wurramala found the whale on the beach. They used stone knives, Garapana. The tail severed from its body, the men then cut the body of the whale into long strips. In (self-) disgust they then threw the knives out to sea. This formed a dangerous and potent hidden reef of the same name. Within the design are the bones of the whale on the beach made sacred with the essence of Mirinyuŋu. The directions of the bands of miny’tji (sacred clan design) relate to the sacred saltwater of Yarrinya, the chop on the surface of the water and the ancestral powers emanating from it. Fratricide, the stench of death, slicks of fat and blood and swarms of flies, regret and grief. With the eventual cleansing act of the knives being flung into the sea.

The whale’s tail is seen as Raŋga, sacred ceremonial object, and employed in ceremony. The bones of the whale are also said to have become a part of the rocks in the ocean. Bones are thought of as the essence of a person. From this description it is evident that the rock and the whale are combined in a spiritual manner which is extremely significant to Munyuku people. There may be some echo of a reference to a related Munyuku icon, the anchor— a symbol of rock-like foundation for the family.

It is inherent in the songs that these rocks/bones are powerful but invisible to those without knowledge. Barayuwa’s solution to representing this place is inspired. He makes the bones, knives, anchors and then submerges them beneath the water of that design.

It was in 2013 that Barayuwa started to hide the elements of the whale skeleton in this style of work. A work in the NATSIAA of this year was Highly Commended by the judges and caught the eye of the Director of the NGA Ron Radford who commissioned a similar work. An installation which was exhibited at the NCCA in Darwin at the same time as his last Outstation show led MCAA Director Liz-Anne McGregor to commission a conceptual wall work for their permanent collection.

There is perhaps a hidden reference to the dangers of overconsumption. The resources of highly prized fat in a beached whale are equivalent to gold in a hunting society. But in the temperatures and conditions of the Top End, the dangers of contamination are real. A decomposing whale can become a literal bomb and the internet shows videos of massive explosions when the stomach cavity is pierced releasing the pent up gases.

We do not have to consume everything just because it is there. The discipline not to can be a life saver.

– WILL STUBBS, Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

IMAGES: Exhibition installations at Searcy Street Gallery, Darwin 2018. Photography by Fiona Morrison.

Works on bark

This exhibition comprised 29 artworks including bark paintings, larrakitj and wood carving. A small selection of the barks are shown here.